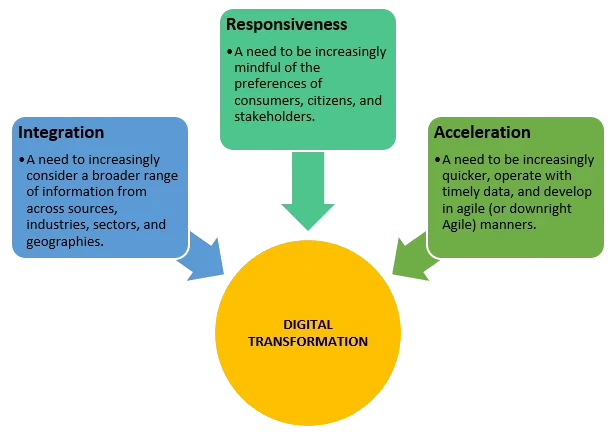

The most general drivers of the digital transformation are companies’ and organisations’ need for integrating information from across an ever-increasing number of areas and activities, responding to users’, customers’, and stakeholders’ preferences and expectations, and acting in increasingly accelerated manners.

Transformational currents

Other lower-level drivers exist.1 However, these three needs seem to be influencing how all organisations approach the digital transformation.

They are always present. Like oceanic currents.

Figure 1: Top-level needs driving the digital transformation.

Figure 1: Top-level needs driving the digital transformation.

Integration2

Organisations are increasingly aware of the negative effects of having data siloed across different levels of an organisation, industry, or sector. Additionally, digital interconnectedness is on the rise alongside the need to operate digitally and enable interactions across regions and between organisations. Furthermore, numerous organisations are now interested in measuring the social and environmental impacts of business activities, which requires assembling very different kinds of data.

As a result, organisations now need to find and integrate increasingly large sets of data, of different types, and from an increasingly broader range of sources.

Responsiveness3

Interest in personalised solutions tailored to the needs of individual users is on the rise. Additionally, transparency demands are shifting from general-level expectations to a desire for granular data. All the while, the world is becoming increasingly polarised, which means pressure to respond to stakeholder demands is also rising.

As a result, organisations must at least partially use any data they gather to understand and respond to consumers’, citizens’, and stakeholders’ expectations.

Acceleration4

The speed of human interaction has increased steadily, with many interactions now taking place in the span of seconds. Additionally, inter-sectoral effects are now faster than ever, and example how COVID’s impact on supply chains was almost immediate. Not to mention the technology sector itself is characterised by a “break things fast” mentality that explicitly calls for organisations to act and develop speedily.

As a result, organisations now face a need to be increasingly quicker about everything, operate with timely data, and be “agile” in their own development.

Awareness pays

Digital transformation projects in any organisation will be influenced by these three transformational currents independently of whether implementers are aware of them or not.

Implementers unaware of these three transformational currents are like sailors trying to navigate the sea without understanding how oceanic currents work.

Implementers aware of the transformational currents do not have success guaranteed, but they do benefit of the ability to make informed choices.

—

Footnotes

-

See, for example, C. Ebert and C. H. C. Duarte, ‘Digital Transformation’, IEEE Software, 35/4 (2018), 16–21; S. Nadkarni and R. Prügl, ‘Digital transformation: A review, synthesis and opportunities for future research’, Management Review Quarterly, 71/2 (2021), 233–341. ↩

-

For more about this, see, among many others: A. Day, ‘Six steps to solving the sustainability data challenge’, (2021); Government Analysis Function and Office for National Statistics, ‘Joined up data in government: The future of data linking methods’, (2020); S. Mirsattari, ‘Solving ESG data integration challenges at a critical moment Insights’, (2022); J. Patel, ‘Bridging data silos using Big Data integration’, International Journal of Database Management Systems, 11/3 (2019), 01–06; R. Reda, F. Piccinini, and A. Carbonaro, ‘Towards Consistent Data Representation in the IoT Healthcare Landscape’, Proceedings of the 2018 International Conference on Digital Health, (New York, NY, USA: Association for Computing Machinery, 2018), pp. 5–10; A. Kadadi, R. Agrawal, C. Nyamful, and R. Atiq, ‘Challenges of data integration and interoperability in big data’, 2014 IEEE International Conference on Big Data (Big Data), (2014), pp. 38–40. ↩

-

For more about this, see, among many others: L. Ardissono and A. Goy, ‘Tailoring the Interaction with users in electronic shops’, in J. Kay (ed.), UM99 User Modeling, (Vienna: Springer, 1999), pp. 35–44; FSA, ‘FSA Covid-19 Horizon Scanning: Social Media listening’, (2020); E. Heims and M. Lodge, ‘Customer engagement in UK water regulation: towards a collaborative regulatory state?’, Policy & Politics, 46/1 (2018), 81–100; M. Karampela, E. Lacka, and G. McLean, ‘“Just be there”: Social media presence, interactivity, and responsiveness, and their impact on B2B relationships’, European Journal of Marketing, 54/6 (2020), 1281–1303; C. Koop and M. Lodge, ‘British economic regulators in an age of politicisation: From the responsible to the responsive regulatory state?’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27/11 (2020), 1612–35; M. Matarazzo, L. Penco, G. Profumo, and R. Quaglia, ‘Digital transformation and customer value creation in Made in Italy SMEs: A dynamic capabilities perspective’, Journal of Business Research, 123 (2021), 642–56; M. Munir, M. S. S. Jajja, and K. A. Chatha, ‘Capabilities for enhancing supply chain resilience and responsiveness in the COVID-19 pandemic: exploring the role of improvisation, anticipation, and data analytics capabilities’, International Journal of Operations & Production Management, 42/10 (2022), 1576–1604; C. Reh, E. Bressanelli, and C. Koop, ‘Responsive withdrawal? The politics of EU agenda-setting’, Journal of European Public Policy, 27/3 (2020), 419–38; H. Yoon, D.-H. Shin, and H. Kim, ‘Health information tailoring and data privacy in a smart watch as a preventive health tool’, in M. Kurosu (ed.), Human-Computer Interaction: Users and Contexts, (Cham: Springer International Publishing, 2015), pp. 537–48. ↩

-

For more about this, see, among many others: J. A. Bolanos and A. Guter-Sandu, ‘Governments are demanding more and faster data than ever. That carries risks’, (2020); A. Lorentz, ‘Big data, fast data, smart data’, (2013); K. Yeung, ‘Algorithmic regulation: A critical interrogation’, Regulation & Governance, 12/4 (2018), 505–23; K. Yeung and M. Lodge, Algorithmic Regulation, (Oxford University Press, 2019); L. Andrews, B. Benbouzid, J. Brice, L. A. Bygrave, D. Demortain, A. Griffiths, M. Lodge, A. Mennicken, and K. Yeung, Algorithmic regulation, (2017); A. T. Chatfield and C. G. Reddick, ‘Customer agility and responsiveness through big data analytics for public value creation: A case study of Houston 311 on-demand services’, Government Information Quarterly, 35/2 (2018), 336–47. ↩