All organisations have a culture. This culture influences everything they do. Many believe managing said culture can help improve organisational outcomes, but managing an organisation’s culture can be hard due to the fact that aspects of this culture are incredibly had, if not impossible, to observe.

Foundations

A necessary first step to thinking about the culture of an organisation is visualising it and measuring it.

There are tons of literature to help with this challenge. Since this is a blog post and not a journal article, I’ll limit myself to three absolutely necessary mentions.

In my view, the rhree foundational references needed in any conversation about organisational culture are Weick, Schein, and Sackmann.

- Weick taught us that organizational culture is a dynamic construct that can change suddenly, especially in the face of unexpected events.

- Schein is linked to the idea that organizational culture has visible, declared, and invisible aspects (which are incredibly difficult to measure).

- Sackmann stressed that an organization’s culture is not unitary but, rather, an amalgam of subcultures at various organizational levels.

The sum of these and many other lessons in the literature is that good management of an organization’s culture can indeed improve the results that the organization obtains in a non-deterministic way, but even the best cultures can fail surprisingly, and fully measuring an organisation’s culture is incredibly hard.

Paradox

Sometimes incidents/accidents happen because the signs of a bad organizational culture are ignored. Bad attitudes, for example, eventually lead to poor management of objectives.

However, sometimes things happen because some problem in the culture of an organization was missed.

One way to address this paradox is to try to improve how one measures organizational culture, on an ongoing basis. It is worth supporting efforts in this direction, especially now that data can be analyzed in ways that were not possible before.

However, everything has a limit.

When it comes to organisational culture, something will always be missed.

Dealing with uncertainty

It is therefore important to develop mechanisms to detect the existence of possible unknown aspects of an organisational culture that might develop into problems.

I am not talking about measuring what cannot be measured. This would be a contradiction. As I said, certain aspects of an organisation’s culture will always be missed.

I am talking intead about being alert to signs that there is something that is not being measured.

I think this could be possible to do by measuring misalignment between the different known aspects of an organization’s culture.

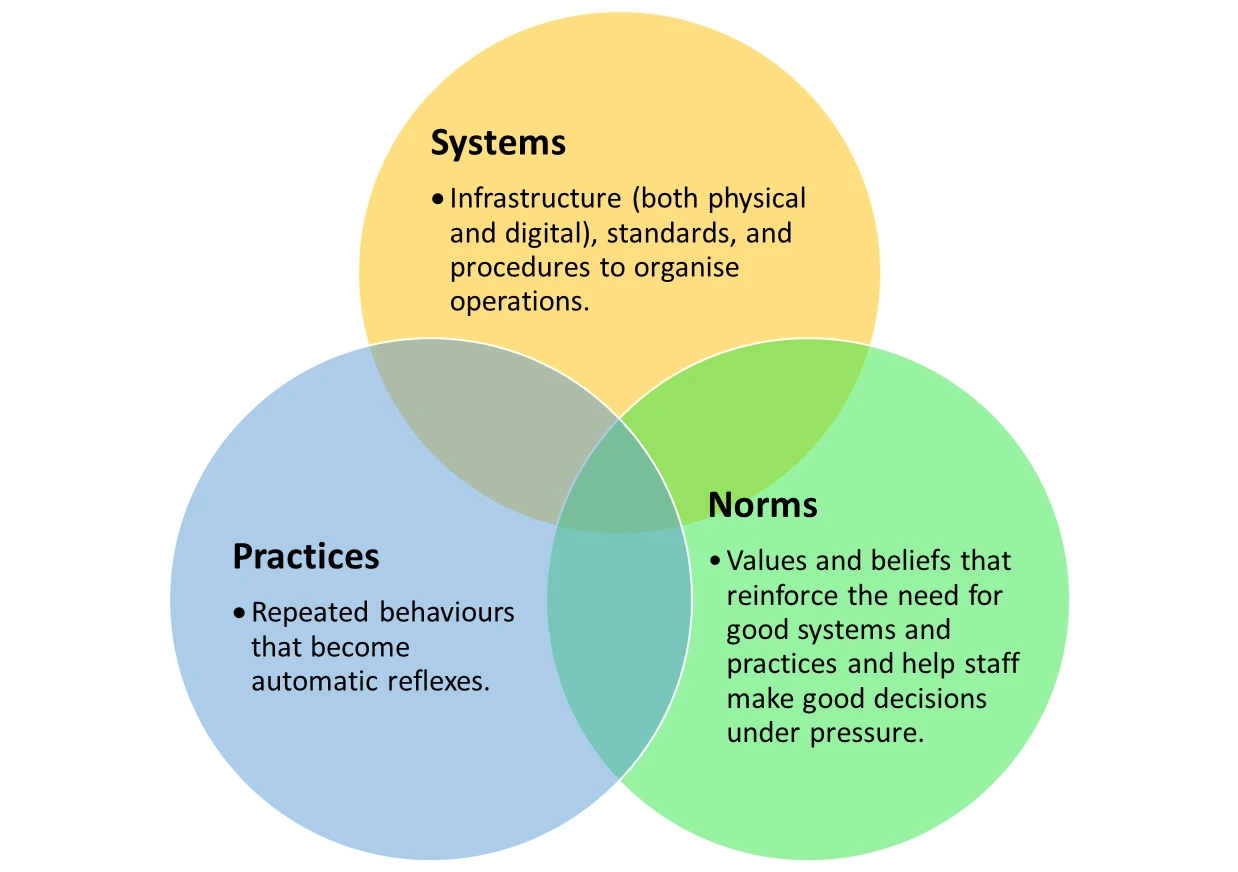

Organizational culture can be conceived as the intersection of dynamics related to three concepts: systems, practices/behaviors, and norms (Figure 1).1 A healthy organizational culture involves positive reinforcement between the three aspects.

Figura 1. The three faces of organisational culture.

Figura 1. The three faces of organisational culture.

It stands to be reasoned that even if one cannot see what is unknown, one may potentially gauge the effect of unknown organisational culture dynamics by testing alignment between the different faces of said culture.2

If the data an organisation holds about itself shows consistency across the different faces of organisational culture, the room for concern about unknown dynamics is lower than if the data shows tensions between them.

Next steps

I reckon the above could be implemented via an algorithm that takes data from many areas an organisation and searches for endogeneous reinforcement patterns (or the lack thereof). This is something I have wanted to do for a while.

—

Footnotes

-

Adapted from Bolanos, J. 2020. Organisations, culture, & food safety. FSA. ↩

-

It’s hard to reference this paragraph accurately. The idea is a mesh of my published views and conversational brainstorming with Lone Jespersen, an expert in organisational culture in the food sector. Figure 1 comes directly from my research, alongside the interest in feedback across categories. She suggested visualising the sets as moving towards one another as maturity increases, which I think was a beautiful way to imagine the process. ↩